Literary Cities

Literary Cities

Literary Natal

Brendan Zietsch sends a Literary Postcard from Brazil's cultural cradle. Obscure, impoverished, difficult to get to for almost everyone in ...

Read MoreThis is a Literary Cities postcard from Karratha, by Megan Hippler.

When my employer in San Francisco sent me to Karratha for a month, they didn’t know their algae farm on the edge of town held a growing community. The dirt was the brightest red I’d ever seen, the kangaroos and jabirus strolled between our ponds alert but fearless, and the sky was grand without the high rises or mountains I’d always known. The location was stunning, but the people made it worth staying. We spent our days in labs, in ponds, or monitoring centrifuges, but in the evening, everyone but management wandered back to the crib room and our dongas, the portable buildings divided into single bedrooms. There, we became people again. We danced on the sidewalks, coordinated to find the snake living under the dongas, and dragged our desk chairs into the parking lot to watch the satellites cross the sky.

That July dragged on in the best way it could.

Back in San Francisco, I stunned my employer when I asked to return to Karratha immediately. They had never sent anyone happy to stay for an entire month, so they weren’t going to let it pass if I wanted to move there indefinitely. I spent the time in America filing for visas, packing up the apartment, messaging the friends I’d left in Karratha, and dreaming of the laughter in the kitchen, the goannas in the shed, and the people I wanted to see again.

By the time I returned, the community had grown and become even more international as backpackers flocked to the site to complete the hours of rural work required to extend their visas for another year. They analyzed samples, maintained pumps, or raked algae paste in the scorching heat.

We had the Filipino painter who transformed the bathroom in her shared donga into a place to make her oil-painted portraits come to life until the fire marshall ruled two people couldn’t share dongas anymore. The American woman on night shift made her own pasta and cakes, and once made crepes at midnight for anyone still in the kitchen. The Irish carpenter built a deck to extend our living space and a functional pool table to keep us entertained. The French artist painted the inside of his camper van while the French hairdresser had a line of people asking for cuts and dyes. The Portuguese man cooked for anyone around, and the Australian sparky helped us set up the movie projector we would pinch from the conference room each night to broadcast sports matches from Premier League Soccer and Irish hurling to Indian cricket and Rugby Union.

We were all people intentionally displaced from our homelands sharing a single kitchen.

Playing golf became popular for a while as we hit balls from the elevated cyclone-safe land toward the evaporation ponds. Someone was always ready for a game of Spoons or Uno or Cards Against Humanity, and we often played the same board game three or four times a week.

We tended to stay on site because it was comfortable, but we knew our town too. The painter had a joint show in the visitor’s center, the community garden volunteers knew some of us by name, and we often huddled in our company fleeces on picnic blankets at the outdoor cinema. We’d scatter to the beaches or the boats sometimes to cool off and breathe.

And in the midst of all this was me, the writer. I found my voice as I scrawled poems about the way the sun set so fast you could see it move, how the moon curved like a smile, and the way we all ran out into the yard laughing with delight the first night it rained after six months of dust. I wrote postcards about the butcherbird we called “Norman” vigilante over our lunch table, the feral kittens that broke our hearts each time someone found one drowned in a pond, and how we delighted when the swallows returned to ride the gale winds for a few days before migrating onward.

I took over the company newsletter, where I wrote about the animals we saw every day, the things to do in the neighboring towns and parks, and fun facts about one another. I needed the people who lived with me to realize where we were. I wanted them to see the details of our community, the little things that made it work. I wanted to bring us closer together, even though we didn’t need it.

I stayed in that donga long after our community grew so big the frogs stopped living in my toilet tank, and I would have stayed longer if the company hadn’t closed the site. They said it was too expensive to keep running in Karratha, so we scattered back across the world. Some of us settled down and some are still traveling years later, but whenever any of us meet again, we retell the stories of what we did on those long dusty days in Karratha. Then, we tell each other everything we know about our former colleague’s successes, because Karratha was more than just a time when we grew algae in rural Australian. It was our home.

This is a Literary Cities story, part of a series where writers reflect on the places and experiences that have inspired them. To read more like this, click here.

For more like this, and the rest of our signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Megan Hippler is a writer from West Virginia who currently lives in Australia. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Seamwork magazine, Parent Co, Beyond Your Blog, and Modern Loss. When she’s not writing about her life, she’s likely exploring the Australian wilderness with her partner and their rambunctious dog.

Literary Cities

Literary Cities

Brendan Zietsch sends a Literary Postcard from Brazil's cultural cradle. Obscure, impoverished, difficult to get to for almost everyone in ...

Read More Literary Cities

Literary Cities

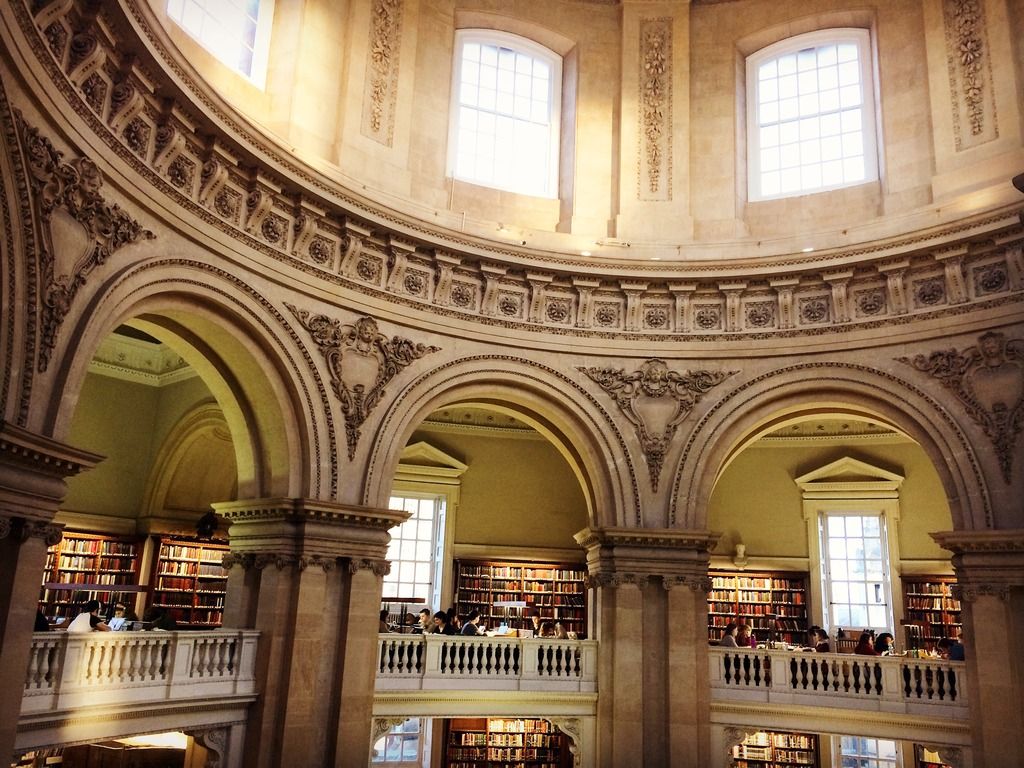

This is a literary postcard from Oxford, by Rebecca Slater. I came to Oxford to write. I tell myself this most mornings, particularly these dark ...

Read More Literary Cities

Literary Cities

Claire Rosslyn Wilson, on the beauty in the burning fires of Valencia, Spain The smoke is there the next day, caught up in the threads of clothes ...

Read More