Justin Heazlewood, author of Funemployed, on the family frustrations unique to artists.

One of the first artists I ever saw on TV was Mr Squiggle. He was an eccentric, spacey illustrator with a pencil for a nose. During his drawing segment he would get distracted and drift skywards, crying, ‘Spacewalk time! Spacewalk time!’ His minder, Miss Jane, would take a hold of his leg and guide him back down to earth. This symbolises the artist’s relationship with their family. When they’re at risk of drifting too far into the clouds, family is there, tethering them to the stove of reality. Every show needs a director, and your parents are the first executive producers of your life. It’s a complex working relationship, which often leads to tension over creative differences.

My nan was the passionate director of my early dreaming. At the pivotal age of twelve, as we sat by the fire of her flower beds, she filled my head with big ideas and hard truths.

‘You have to have a dream.’

‘Only the strong survive.’

‘The Greens are going to ruin Tasmania.’

Not so much the last one.

At twenty-two, when I made a choice to pursue my artistic career, she cautiously approved, though she did warn me, ‘You’ve chosen a very hard path in life.’ My only-child ego took this as a compliment. I was a trailblazer, a leader, cut from different cloth – just like she’d been telling me my whole life.

At twenty-five, after my pissy Comedy Festival campaign, Nan went quiet on the phone. ‘When you get home we’re going to have to sit around the table and have a talk about your future.’

Good grief. Here was the woman who’d spent my entire childhood telling me I had to have a dream – now she was serving the fine print telling me that said dream should be deferred if not profitable within the first three years. This sudden repression only made me more determined than ever to persevere. She’d created a monster.

Parents of artists face a paradox. They want their children to have the freedom to pursue their passions, but they also want them to be financially secure. It must be perplexing to see us basking in our dalliances, no longer programmed to work full-time or have children in our early twenties – especially for Nan’s generation.

Cartoonist David Blumenstein says he has copped plenty of attitude from his family over the years. ‘Dad will say, “It’s not too late for you to go into a business course,” every time I’m unemployed, which is all the time. Well, look, they’re nice parents, and they want me to live. I was fine for a few years, then they started saying, “How are you going to get a mortgage?” On what I make and the amount of time I’m employed a year, I probably can’t. Their attitude is, “Well, that’s not acceptable. You’re going to have a family. You’ve got to provide for your family.” If I get a job tomorrow, I won’t hear about it for a while.’

David recently married fellow comic artist Sarah Howell and says he’s fighting for two now. ‘I don’t want to look like a pussy in front of my wife. So, instead of keeping my mouth shut, I tell Dad what I think, and so we get in more arguments now.

When he’s saying to me, “You shouldn’t be doing this,” well, Sarah shouldn’t be doing this either. I say, “We are and we do. And this is why, and this is what matters to me.”’

David recalls an instance where his dad introduced them as ‘these two fools, they play with comics’.

‘The worst one recently was when I tried to equate what I do with what he does. He started off studying economics and law, but dropped out to build high-performance engines in the backyard with his brother. They made that their career. They love it and it’s hard work, and it’s been patchy over the years. I dared to suggest that what I was doing was a bit like what they were doing. He got very angry. To him what I do is pissing around – playtime.’

Theatre-maker Benedict Hardie says there is an unspoken anxiety amongst male artists who feel emasculated because of their meagre incomes. ‘They’re around thirty and they’re not making an income so they feel like they can’t propose to a girl because they’re not a man.’

Angie Hart says that respect and recognition are often what Australian artists crave most. After a round table discussion with former arts minister Tony Burke in 2013, she said one of the biggest issues was artists not being taken seriously.

‘From being asked to be visibly seeking employment from Centrelink when you already have a career, to being asked if you are still doing the “music thing”, as if it is a pipe-dream that you will eventually come to your senses from.’

As Sydney writer James Brown wrote in the Lifted Brow, ‘I think being able to compose music for contemporary dance would put me on the low priority list if there was an apocalyptical situation in which society broke down and people were chosen to be saved or fed to other people or left to die.’

A lack of education about the arts can be a vicious cycle, especially when parents are the ones psyching their children out of becoming an artist. One drama teacher I spoke to said that a student who loved acting had dropped out because it didn’t offer enough points in VCE (he wanted to be a doctor).

Oscar-winning animator Adam Elliot says parents need to be more encouraging of their children’s artistic endeavours. ‘When I go to schools a lot of parents get in touch with me and say, “My husband and I are really worried, my child is showing signs of being creative – we want him or her to have a stable career.”I mean, who doesn’t? But the sky’s the limit when you’re an artist; we’re not restricted by wage caps. Films can make a billion dollars. The odds are stacked against you, but who’s to say your child isn’t going to be brilliant?

‘I remember when I said to my parents that I wanted to be an animator,’ he tells me. ‘They just stared at me. They didn’t even know what an animator was. When I started playing with plasticine, they just gave up. My older brother is an actor so they were quite relieved when my younger brother told them he wanted to be an engineer. He’s the black sheep in our family.’ He laughs.

In 2011 theatre-maker Bron Batten found the best way to connect with her parents was to involve them in a show. In Sweet Child of Mine, Bron performed alongside her sixty-year-old non-performer father. Bron says she realised she was partly responsible for the shortfall in understanding. ‘I’d excluded them from it because of that lack of understanding – we didn’t have a way to talk about what I did.’

I’ve often wondered what it would be like to have artist parents. I spoke to Helen Marcou and Quincy McLean, organisers of the Save Live Australia’s Music (SLAM) rally. Quincy has been a musician for thirty years, and while his sixteen-year-old son is keen to follow in his footsteps, they’re both cautious. Helen says, ‘He’s got a big interest in science and all we say is, “Look, it’s a growth area, science,” and it’s a good way to make you a well-rounded person and possibly sustain your musical career.

‘We’ve had to be really honest with him. At times he’s said, “I want to drop out of school; I want to be a musician.” We’ve said, “Look, you’re really cutting off your future chances if you do it at sixteen. You might change your mind.” We’ve seen the struggle; we’ve seen the alcoholism. We wouldn’t discourage him from doing it at all. We’d say do it, but be aware. And don’t make us your drivers. Get your bloody licence.

‘I’ve said, “You want to be a good songwriter? At your age now you’re having a conversation with yourself, you haven’t experienced the world through learning and study and knowledge and experience,”’ Helen adds. ‘“That’s where you’ll be able to have conversations with the rest of the world.” His lyrics at the moment are about “my mum and dad hate me”.’

Filmmaker John Pace comes from blue-collar Townsville and says his recent inclusion in the family tree says everything. ‘My aunty did a family history from 1750. It was John Pace all the way to my Grandpa Albert, who named his son John and started again. They were all mechanics – ship mechanic, mechanic, all the way down to panel-beater. The last name was me and the occupation was blank. One part of me was so sad. They could have put something.’ He laughs. ‘That means I’ve almost achieved an impossible feat of leaping out of hundreds of years of history of what I’m supposed to do.’

As I mentioned earlier, I was the first in my family to go to university. There were high expectations that I would get a high-paying job (journalist), earn a full-time wage, eventually take out a mortgage and buy into the Australian dream. I can only imagine the mixed emotions when I ask to borrow money ten years on. My phone conversations with Nan often end in her saying, ‘One day you’ll make it.’ I know she’s only trying to help – but part of me finds this message belittling. I want her to acknowledge how much I’ve achieved and how successful I am now. Your family doesn’t have to love what you do, but it’s important that they learn to respect your commitment and integrity.

At the heart of respect is mutual understanding. There is a great divide between artists and the community around them – at the heart of that divide is a misunderstanding about money. In our capitalist society, money is the first measure of success – yet for Australian artists, it is perhaps third down the line behind artistic goals and industry recognition.

Benedict Hardie articulates the frustration of family. ‘They think there’s this moment where the dam will burst for a creative person. “Oh yeah, but once you get to a certain point and you’ve done a certain amount of TV appearances, suddenly the money will roll in and you’ll buy a house and you’ll have all the stability you need.” And they’re always saying, “Don’t worry, it’ll happen, it’ll happen,” and I tell them, “No it won’t,” and they say, “Oh, don’t talk like that,” and I say, “No, I’m not talking like that, I’m not poo pooing myself. I’m aware of the reality. And I don’t want to sign up to do this on the proviso that I’ll one day make money from it. I signed up to this in the knowledge that I will never make money from it. And if I do it’s a bonus.” It’s pretty negative,’ he concludes.

Family can’t always give us the feedback we crave, but we can learn to appreciate their loving energy. Sometimes Mum will surprise me by quoting my lyrics back at me. ‘I’m so post modern I write reviews for funerals and heckle at weddings from inside a suitcase.’ She bursts into giggles. In an interstellar burst, she understands my universe. After our volatile past, there’s nothing more healing than being able to share my world with her. Perhaps she’s holding on to my leg not to pull me down, but to be lifted up.

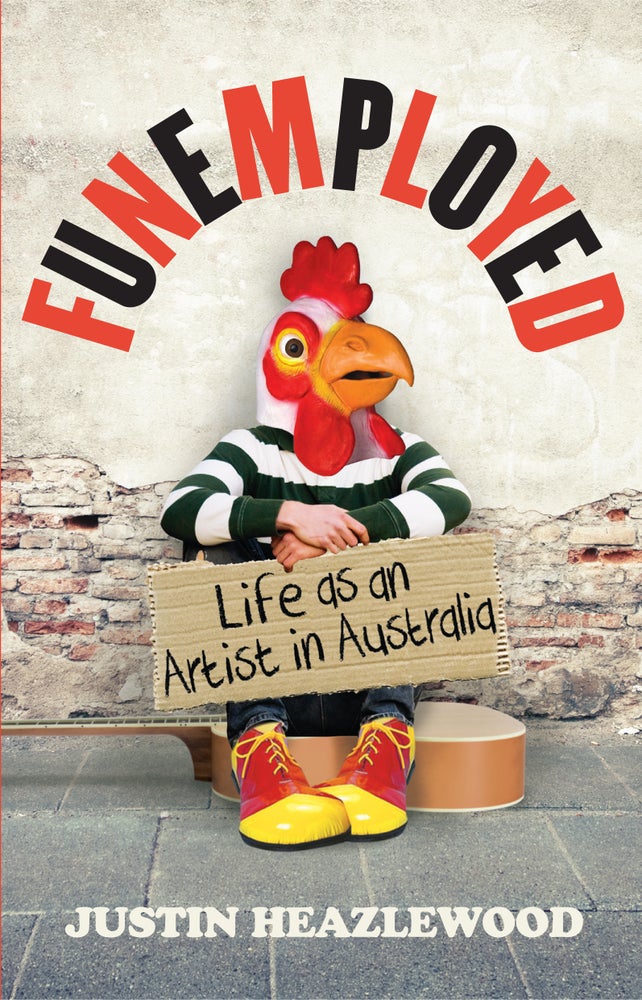

For More Advice On Life as an Artist, Read Justin Heazlewood's Funemployed

Click To Buy

Justin Heazlewood is performing his Cat Show at Perth Fringe, opening Monday. Check it out here.

Justin Heazlewood

Justin Heazlewood a writer and musician who first found fame as The Bedroom Philosopher. He has also written two critically-acclaimed books: the memoir The Bedroom Philosopher Diaries (2012), followed by Funemployed (2014), which focused on the ecstasies, horrors and realities of being a working artist.