A Writers Bloc workshop feature.

We Saw Through the Same Eyes

by

Myles Gough

It wasn’t the first time that death had brought Sean back to his childhood home.

As he stood in the living room, with its earthquake cracks running down the orange plaster walls, and the stacks of nonfiction books from Publisher’s Clearinghouse, he thought about the last time he returned.

More than a decade earlier, an email had come from his sister, Amy.

Sean had read it in the hostel lounge.

It’s Andrew, she’d written. The only other word he remembered was ‘suicide’.

Sean’s extended family had spoken in whispers.

They gathered in tight circles inside the funeral home, its sterile smell lingering, an amalgamation of flowers and cologne and cleaning products.

Sean had stood in a daze between his mother and Amy, whose blue eyes had brimmed with tears. Andrew’s corpse locked inside a mahogany cage across the room.

He had watched his aunties, in their black knee-length skirts, smearing together makeup and tears with dark handkerchiefs, and taking bird-sized bites from neatly cropped sandwiches. His uncles, with their heavy guts bulging over their belts, shook his hand authoritatively, forceful, as though they needed to impress upon him the crushing weight of a brother, lost.

It had seemed familiar, standing there, as though someone was playing a cruel joke, had filmed their lives. Only on this viewing they were down one more cast member. Another cartoon face slammed down, eliminated, like in a game of Guess Who?

Andrew’s was the second funeral in as many years.

His dad’s brain tumour had acted swiftly, and when the hospital ethics committee denied the surgeon’s request to perform an experimental procedure, his fate was sealed. He decayed, comatose. Dead at 57. They'd held the memorial service in that same room.

*

Sean knew his parents, at a blurry and indefinite point in history, had cared deeply for each other. There was photographic evidence lost in dusty photo albums stacked on basement shelves: his dad’s moustache and seventies-era sideburns that came down to his jawline, and the wavy blonde hair that fell in wisps over his forehead; mum in bellbottom jeans, straight black hair falling past her waist, dark eyes full of excitement and wonder. But marriage, or life, or both, had eroded their passion.

She was prone to bouts of exhaustive sadness, and his father turned inward too, focussed on his work. They had allowed their differences to expand like an ever-inflating lung, inhaling dust and carcinogens, building up between them like an impregnable wall. An insidious silence crept through the house, sprouted from the floorboards, grew on the walls like vines.

It was spring when his dad eventually left.

For the first few months, Sean and Andrew would take the subway uptown to visit his new apartment on the weekends, leaving Amy with their mum, who pleaded with her to stay, bribed her with trips to the mall and the movies.

Sean remembered drinking cold beers on the balcony, and sleeping over on the second-hand sofas they’d helped their dad salvage from outside a neighbouring building. He remembered his dad, happier on those nights, a stranger—someone he didn’t quite recognise, liberated. He also remembered waiting up until after his brother fell asleep, listening for the sound of his breath, needing to hear the regularity of it, to see his naked chest, ribs, rising and falling.

It was barely winter when they discovered the tumour.

Sean resented his mother for driving his dad away in the first place, and for making him feel like a stranger in their home when he returned, after the diagnosis. And he was angry at his father, for giving up on their family, for choosing solitude, and for not fighting harder to stay alive. His parents tried to love each other again, in the hospital, in the days when everything was close to lost, but it was too far gone.

Everyone was to blame, and no one. Sean’s solution was to leave.

At the time, he didn’t think about how it would affect his siblings: he knew they were sad, and frustrated, but he didn’t question the depth of their grief. Andrew had been focussed on finishing high school and applying for universities. And while Amy had loved her dad, she was much closer with their mum. She was still so young, the scars would fade, she’d be alright, he thought.

Sean didn’t exactly run away—he phoned occasionally from the road. In his mind, it was a temporary escape. There was a tether that would lead him back, eventually, to find a job and start a family of his own.

Would things have been different for his brother had he stayed? He sometimes wondered.

*

In the days after Andrew’s death, neighbours deposited pre-cooked casseroles, like abandoned babies on the doorstep of their home. When Sean or Amy opened the door, they’d make a brief handover, reciting lines from a rehearsed script, before scrambling back down the steps and the walkway, out of sight. The instructions for reheating the casseroles were always neatly spelled out on a sticky note, or a crisp sheet of lined paper, and taped to the foil cover.

Many things had warped into a blur over the years, but the memory of those deliveries remained vivid. He hated that awkwardness: the uncertain silences, the sympathetic glances, the bumbled words.

In the autumn nights following their brother’s death, Sean and Amy would sit on the back porch, listening to the suburban quiet; the whirr of cars on the main street, two blocks away, and the almost inaudible electric hum of the streetlamps—a quasi-silence interrupted only occasionally, by the baritone bark of the neighbour’s German shepherd.

Sean would roll a small joint, taking long drags until his smoke-filled lungs felt heavy, and ached. They would sit for long stretches, talking about their brother, watching each other’s faces distort in the flicker of candlelight. Were there warning signs? Sean would ask, and Amy, still in high school, would just shake her head. He always seemed happy, she used to say, closing her eyes.

They talked, on other occasions, about their dad, before he left, recalling memories of him at work in his garage, in his grease-stained lab coat, and their mother’s depression, saying how sad it all was. A husband, and a son. Both gone.

“She never stopped loving dad, you know,” Amy said, matter-of-factly one evening. A judge setting the record straight, instructing jurors to dismiss what they thought was credible, convictable evidence. After a long pause, “I worry about her, Sean,” she said. “She’s getting worse now.”

Since returning, Sean had noticed it too. She was waking in the very early morning, moving from room to room like a ghost. Halfway gone but somehow anchored to this hollow place, examining artefacts, tracing teardrop fingertips along dusty surfaces, clinging to the memories that resided in the walls, the skeleton of the house.

Sean wondered how it all affected Amy.

He was wrong to think she was too young to carry the weight of their dad’s death, and his absence; the dissolution of their family. But she had watched her brothers over the years, learned from their body language, and was careful not to reveal too much of her own emotion in how she behaved. To Sean, she was an enigma.

Still, on those nights, they had made promises to look out for each other. They were pacts for the future that felt real, held substance—even if they too were destined to dissolve.

When the silences got too long, too meditative, Amy would yawn and stand up.

She’d lean over and touch her brother’s shoulder. Get some rest, she would say, before going inside to bed.

But Andrew’s death had left Sean in a sleepless haze, which lasted through the winter. He had grieved when he lost his father, and he was angry for a time, but the reality was plain: there was no fighting the cancer. It was relentless, and shitty, but unavoidable. Sheer bad luck.

His brother’s death, on the other hand, was deliberate. He made that choice. It was that fact that haunted Sean more than anything. The two of them had grown up close, just more than a year separating them in age, and their upbringing had been almost identical. What had grown inside of him to compel that act?

Sean had demanded to see his brother when he got home, just before the funeral. His skin was pale, and cold to touch, and the violet bruises, like long intersecting fingers, were still visible on his neck underneath the concealing makeup, and his collar; the signature of strangulation, an orange extension cord.

His brother’s death defied the natural order of things. In those brief moments, standing over him, Sean glimpsed his own mortality.

Andrew was gone. The ease of it was troubling.

On those sleepless nights, Sean would wander, often for hours at a time, completing long circuits around the neighbourhood. He’d head south to the waterfront, watching the shaky reflection of the moonlight, a white carpet unrolled from the horizon, lapping against the drift-wood covered shore.

When the spring came after Andrew’s death, and the city thawed, Sean packed a bag and boarded a bus for Los Angeles. Amy came with him to the terminal, rode with him on the subway. I need to drop a resume off at a shop, anyway, she said.

Amy never asked where he was going, or what his plans were, or when he was coming back. She just wanted to be close to him—up until he left, Sean decided. He was happy she tagged along. When they hugged goodbye, she told him she loved him. He kissed her forehead, and told her he'd call soon.

Sean watched from his window seat, on a half-empty bus, as she walked away, into the grey city.

That morning was the last time he’d been inside their home.

*

Sean thought about his final words to his mum. They had spoken on the telephone, briefly, around Christmas. Amy had held the phone to her ear. She kept calling him by his brother’s name, and Amy, in the background, would correct her. “It’s Sean, Ma. Sean.”

He had wanted to apologise, but he wasn’t sure to whom—his mum, or Amy.

“You’re a great mother,” he said, though he wasn’t confident in his memory any more, eroded by time and scrambled by distance. “I love you.”

After a long pause, filled with raspy breathing, she replied. “I love you too, Andrew. It’s so nice to hear your voice again.”

Her funeral was a simple, quiet affair. Only some of the same aunties and uncles were in attendance, diminished in size, and greyer. She was buried in a cemetery near the airport, next to his dad, where the graves were insignificantly marked with flat granite slabs, no elaborate tombstones. At the burial, the minister occasionally went silent, hands folded in front of his midsection, while 747s passed overhead.

In the wake of his mum’s passing, nobody delivered casseroles. Sean decided that it was only customary to do so when death was sudden, unexpected; when others felt shame or guilt for their good fortune, to have lived, and stolen another opportunity to feel the warmth of the sun, the kiss of a lover.

Sean’s memories evaporated as he looked around the living room of his childhood home. Learning about his mother’s death was like watching a news report about a suicide attack killing scores of people in an already war-ravaged country. Sean felt devastated for an impossibly brief moment, but it was too far away to be real. The pain he felt wasn’t sharp or excruciating, but dull and numb. A lurking sensation that something wasn’t quite right. Flying home made it real. Sitting here, made it unbearably so.

He sat on the piano bench in the living room. He touched one of the white keys and the resulting discordant sound, louder than he’d anticipated, filled the room. As it reverberated, his sister appeared in the doorway.

“Is there anything you want?” she asked, startling him. She dropped a cardboard box onto a stack.

“If there is, I suggest you sort out some kind of storage. We need to have everything out of here by the end of the week, so the estate agent can start showing people through.” Her tone was unsentimental.

Sean turned on the bench so his body faced her, but he resisted making eye contact.

“There’s probably some valuable stuff here,” he said. “But, I don’t think I’m in a position to take anything. What would I do with it?”

Amy shrugged, as if to say not my problem, and brushed some stray hairs off her forehead.

“Well, think about it, okay. I’ve posted a ton of things online. Who knows if they’ll sell? And I’ve arranged a dumpster for Friday. Anything that’s still here is going in, never to be seen again. Not in this life, anyway.”

Sean looked up at his sister. She was nearly six feet tall, and despite her slender build, had a commanding presence in the room. Her dark hair was pulled tight into a ponytail, and the skin around her eyes had become dark with fatigue, or stress, or both. But she was strong. He could see it in the veins that bulged in her forearms, and the shape of her.

He felt small in her presence, and a buried guilt, coiled-up and repressed for so many years, sprung to the surface; it had been bobbing like a buoy ever since he had arrived.

“I’m sorry I wasn’t here to help with mum,” he said, “With everything.” The words he wanted to find dried up in his throat, crumbled away and were swallowed. “Thank you for taking care of her.”

“Somebody had to, Sean.” Her response snapped like a whip. Amy's glacial eyes drilled into his, as though trying to decipher some kind of code, carefully deconstructing the puzzle pieces that comprised this man, she didn’t really know. She wasn’t in the mood for his sympathy, or his apologies, or any thanks.

“She went downhill fast,” she added, looking away quickly, as if she had found what she was searching for, and was mortified, or worse, ashamed. “It could have been a lot nastier. For everyone.”

Sean nodded, returning his gaze to the floor, where he felt it was safest. The room fell silent. He admired her courage: she’d been the one to stay, not only to care for their mum—likely to the detriment of her own relationships—but to face up to all the familiar faces, neighbours and old friends at the supermarket and the bank, and the parent-teacher meetings, and the library or wherever the fuck normal members of a community congregated.

She had stayed, he had fled. Like a bird, panicked.

“Right,” she said, “I have to pick Oliver up from school, and then I’m dropping him at Susanna’s place.” She spoke about her step-son in a purely functional way. He and Sean had been unacquainted until the funeral. “Are you sure you don’t need a place to stay?”

“I’m fine,” he said. “I’m meeting a friend for a drink, and then I’ll drive out to the hotel. I’m staying by the airport. It’s good for quick getaways.” He smiled, but his sister didn’t see the humour.

“Okay. You’ve got my number. Ring if…” she paused. “Ring if you need anything, or if you want to come spend time with your nephew.” She collected two forest green garbage bags, filled with clothes and bath towels, which were sitting by the front door and walked outside.

From the window, Sean watched her drive away and breathed a sigh of relief.

*

The hotel bar was mostly empty. There were two men in business suits drinking Coronas and watching the baseball game, indifferently, on a wall-mounted television, and there was a couple sitting down to dinner, reading their menus sceptically in one of the booths, with a window overlooking the parking lot.

Sean cradled a glass of rum and coke in his hands and looked at the clock on the wall. 9:35pm. He had called his friend, the one he planned to meet for a drink, but he’d been called into the halfway house where he worked for an unexpected evening shift.

Sometimes we need extra eyes on these kids, his friend said. Some of them have real problems. He tiptoed around using the word ‘suicide’.

Sean had taken his mum’s car, and driven back to the hotel. On the way, he stopped at the cemetery, but it was dark, and he couldn’t find the plots where his parents were buried. After several minutes of wandering aimlessly, he sat on a curb, buried his face into his hands. The noise his sobbing was drowned out by the rumble of aircraft overhead, and the incessant hum of cars and tractor trailers speeding by on the nearby expressway.

Back at the hotel, he tried to call Tina, hoping she might answer. It rang seventeen times before the line disconnected. He counted the rings, and cursed the dial tone. It had been four months since she told him to leave. Amy had met her just the once, when she visited him in San Diego after finishing her nurses training. He’d been working as a landscaper, and had met Tina through mutual friends.

“Nice enough,” his 22-year-old sister had said, when he asked her what she thought of his new girlfriend. She was nice enough. And he screwed it up, he thought. Sean wanted to hear a familiar voice; someone who knew him and understood his faults, even if that someone hated his guts. He didn’t mind being hated, at least not as much as being judged.

After finishing his drink, he drove back to the house along backstreets, trying to remember the routes through the city he had learned growing up, on joy rides with friends when they first got their licences.

When Sean got to the house, he was surprised to see Amy’s silver SUV in the driveway, a light on inside. He sat in the driver’s seat, unsure whether to go in. He had never intended to exclude her from his life, or planned on her becoming the sole caregiver, but it was him who constructed the tyrannical distance between them. Maybe it was too far gone, too late to break it down? But that was why he came back.

He found Amy on the floor of her old bedroom. She was flipping through the pages of family photo album. “Hey,” he said.

She looked up and, for the first time since he’d been home, smiled. “What are you doing here?” she asked, looking back down at the album.

“I couldn’t sleep,” he said. “And I couldn’t drink either.” He sat down next to her on the floor. “Why are you here?”

“Susanna’s got Oliver tonight. I was feeling lonely,” she said, looking up at him. “And part of me can’t bear the thought of all these memories going to landfill. At least not without pretending to sort through them. It’s nice to pretend to give a shit, hey?”

Sean absorbed the subtle jab like an expert fighter. “There are a lot of memories,” he said, looking around the room, which had been his, once upon a time. Some of his sister’s drawings, from when she was a kid, were still hanging on the walls, framed, and there were even a few stuffed animals on her old bed: a lanky Kermit the Frog, with a missing plastic eye, and a brown monkey with a too-happy smile.

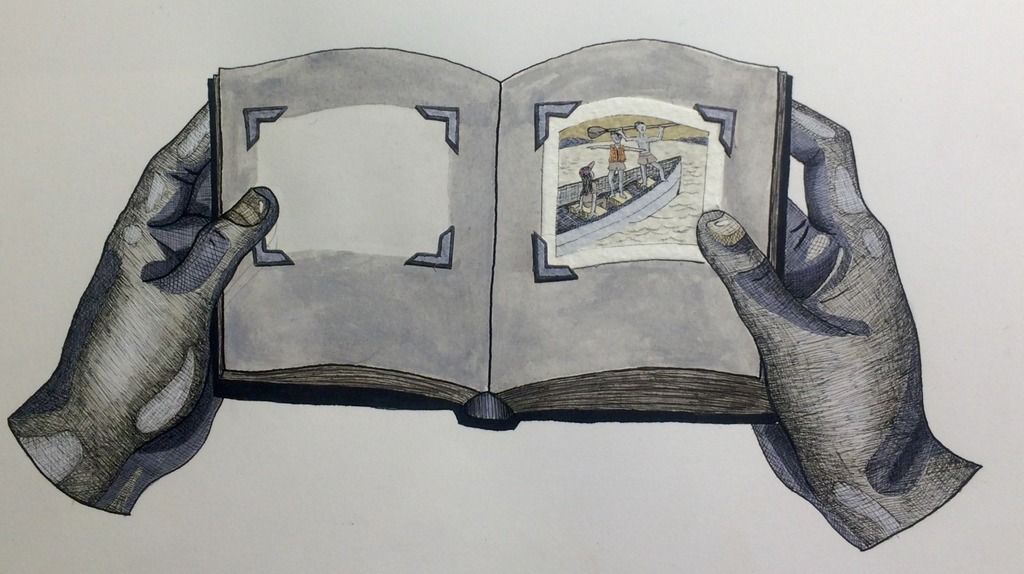

“Do you remember this?” she asked, swivelling the photo album so he could see. Her index finger was pressed against a photo of the three of them, as kids, in a yellow canoe. Sean was standing, bare chested, on one of the seats holding a paddle above his head like a championship wrestling belt; Andrew was in the middle, wearing an orange life preserver, with his arms out like a surfer for balance, and Amy, wearing a pink baseball cap turned backwards, had her head tilted skyward, giggling at some long-forgotten joke, the dimple on her chubby cheek a perfect crescent.

Sean laughed, and nodded. “I’m pretty sure we tipped right after dad took that photo. You probably weren’t so happy after that.”

“You tipped us, you bully,” Amy replied, elbowing him in his side. “Andrew was terrified of drowning, even though it was only a couple of feet deep. And you were rocking us back and forth. He was screaming at the top of his lungs for you to stop.”

“And you thought the whole thing was a riot?”

Amy nodded, and pulled the photo out from its plastic sleeve. When she turned it over they both read their mum’s distinctive cursive. In blue ink it said: Kids frolicking in canoe, Lake Kempshaw, August, 1994.

“She was a meticulous labeller,” Amy said. She placed the photo on a stack she was collecting, and turned the page. There was another photo of their parents, asleep together on a hammock, and one of Andrew, with a too-tall fishing rod, smiling at the camera with a sheepish grin.

“I miss them,” said Amy.

Me too, Sean thought. He wanted to say the words, to share that experience with his sister, but he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Somehow, he felt he hadn’t earned the right. He watched his sister, expecting tears to form in her eyes, to slide down her cheeks; expecting her to elaborate or say something else. But she kept still, eyes trained on the photos.

“I’m mad at you Sean,” she said, after a long silence. “I know I shouldn’t be, but I am. I know you have your life, and that’s fine. But you didn’t have to see mum… wasting away like I did. I was the one. Where were you? Huh? Where the fuck were you?” She pushed him, forcefully, knocking him backward onto his elbows. There was another silence, a frozen moment. The floorboards creaked as he sat back up.

“Tina and I split up,” he said. “That’s not an excuse, it’s just a fact.” He didn’t know how much to tell her, or if she even cared. “She kicked me out and I’ve been living in my car these last few months. I should have come here sooner, but I kept thinking I’d be able to fix things with her. I never should have left after dad died,” he felt tears welling in his own eyes, felt Amy’s handprint like ice on his chest.

“Maybe Andrew would still be here. I’ve been thinking about that a lot,” he said.

“What about me?” she turned to him. “You both left me. And sometimes I’m not sure which of you is worse for it.” Her voice trailed off.

“Andrew is dead, Sean. There's nothing you, or I, or anyone else can do to change that. He was young and he made a stupid decision. No matter how shitty your life is, you still get to wake up every morning. you get to breathe, and fuck, and plant your flowers and your trees.” She looked down at the floor.

“We missed you. Mum, and me. We needed you Sean. We felt abandoned.”

He reached out and touched her hand. “I’m not leaving this time,” he said. "This is home.”

He looked at her pleadingly, willing her to meet his gaze, to see in his face that he meant it; that his words weren’t shells, ornamental on the outside, but altogether hollow. I’m going to be here for you, from now on, he thought.

Amy looked at him, her blue eyes like confused planets, floating in white space. "I don't think this has been your home for some time." She picked up the stack of photos and stood up.

“Relationships fall apart,” she said, placing her free hand on his shoulder. “We’re still family, Sean. We’re all we have left. If you mean it, I want you to stay.”

She handed him the photo off the top, of the three of them in the canoe. At the door she turned. “Get some rest,” she said.

Sean looked at the photo, traced his finger over its slightly faded surface.

He remembered taunting Andrew, and the genuine fear in his brother’s eyes as the canoe tipped, sending their bodies plunging into the dark, frigid water. But Sean had gotten his foot tangled in a line of rope. As the others floated in their life jackets, he remained submerged, kicking wildly and flailing his arms. The canoe was blocking the sunlight, and everything began spinning in a vortex of bubbles, reeds, and stirred-up sand. He was disoriented, overcome with fear.

He surfaced eventually, gasping the sunlight, laughing it off like it was all part of his plan. He never admitted to his brother or Amy how scared he’d actually been.

How scared he continued to be.

I’m going to be here for you, from now on.

The words crept back into his head. A promise. For the first time in a long time, he felt certain about something.

Editor's Note

Myles Gough's short story 'We Saw Through the Same Eyes' is our top pick from this month's selection of workshop pieces. The story wends its way through Sean's intense mental state, drawing his memories together into a wonderfully marbled array of death and all its incomprehensible rituals. These rituals are taken in hand by Sean's sister Amy, who fulfills the archetypal role of the daughter-caregiver while the son is free to escape the same responsibilities. What Amy understands—and Sean fails to comprehend until there is only the two of them left alive—is that death rituals serve a purpose: to allow people to process their emotions and to bind families and communities together after a devastating event.

Edited and selected by Raphaelle Race

MyGo

Myles is a freelance journalist who often writes about science and technology. His work has been featured in the BBC, Cosmos Magazine, Nature, Al Jazeera, the Globe and Mail, and New Matilda. Myles is also a poet and is trying to write more fiction.