What's in a name? Irene Bell explores a history of authors obscuring their identities with pseudonyms.

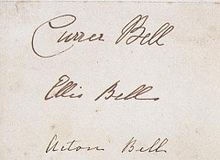

“Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life”—so proclaimed poet laureate, Robert Southey, after Charlotte Brontë gave him her work to read. After this encounter, she published her literary masterpiece Jane Eyre under the pen name ‘Currer Bell’.

Women using noms de plume isn’t a new phenomenon. In the nineteenth century writing as a female wasn’t frowned upon, but a woman earning money was. Publishing under a male name was all that could provide the anonymity they needed to take a step closer to empowerment.

Emily and Anne Brontë, equally talented and defiant of social norms as Charlotte, followed suit and the three sisters became three brothers. All their novels have enjoyed decades of praise. Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell were very talented writers indeed.

Even more famously, after deciding to make her way in the world as a spinster author, Jane Austen published her first novel Sense and Sensibility with the byline “By A Lady”. Her older brother had failed to get her any meetings in London’s publishing houses due to her gender, so her anonymous byline was a very elegant skirting around the problem. Ironically, her debut was so successful with readers of both genders that everyone believed the book must have been written by a man who didn’t want to alienate his female readership. Austen’s second novel, Pride and Prejudice, was credited to ‘The Author of Sense and Sensibility’.

Austen may have become a published author, but let’s not ignore how her oeuvre is viewed by a contemporary readership. These days, with her name sitting underneath her titles, Austen’s books are the emblem of female literature. During their original anonymous print runs, her sardonic novels about English society were enjoyed by readers of both genders equally. Over the centuries, while her novels have remained immensely popular, their reach slowly diminished. Now, by focusing so forcibly on the love-story aspects as opposed to the snarky social criticisms in her marketing, we have stripped her of a large portion of her readership.

On the other side of the spectrum, ‘Mary Anne Evans’ is not a name you are likely to find on any book covers. Evans continued to publish under ‘George Eliot’ even after her identity was revealed, and to this day her work is revered by readers of all genders, even though Middlemarch deals with many of the same themes as Austen’s work.

The problem isn’t a woman’s name—it’s what we believe it insinuates. A 1968 experiment by Philip Goldberg asked the question “what happen[s] when college girls evaluated the same article, half written by ‘John T McKay’, half written by ‘Joan T McKay’?” The disheartening result of the experiment was that it underscored the idea that we see ‘what we expect to see,’—the consensus being that Joan was the worse writer and that the girls were less likely to trust Joan’s research.

It’s now 2017, 200 years after ‘A Lady’ published her debut novel and still female names can feel loaded. A 2014 Goodreads survey shows that 80% of a female author’s audience is likely to also be female—a lot has changed since Goldberg’s experiment, but where are all the male readers? In an interview for The Wall Street Journal, Penguin editor Anne Sowards admits to sometimes asking first time authors to change their names. Publishing is a business and you want to avoid “anything that might cause a reader to put a book down and decide ‘not for me’.”

Despite all this, genre fiction, particularly crime and romance, is a space where female names are advantageous—to such a degree that men are now hiding their identities. With the immense success of female genre writers, from Agatha Christie to Gillian Flynn, publishers want the next big thriller with a feminine touch. An editor was lamenting about this exact desire to British writer, Martin Waites, when Waites said “I could do it.” Thus, ‘Tania Carver’ was created. Carver has now published two well-received thrillers. On her official website, Waites admits to people mostly finding his pseudonym ‘amusing’. Whether all the female authors who have had to hide their identities would be amused by the idea of a man cashing in on their gender is hard to say, there would be too many to ask. Interestingly, the poster-woman for contemporary pseudonyms, J K Rowling, writes her crime fiction under a male name—Robert Galbraith, citing a desire to get as far away as possible from her current writing persona as the reason for the gender-flip.

Still, noms de plume today are overwhelmingly gender neutral. On the one hand, using genderless names doesn’t fix our prejudice, it simply hides it. On the other hand, if everyone used genderless names maybe some sort of equality would be established. While E L James and Harper Lee are women who use androgynous names, S K Tremayne, S J Watson and C W Gortner are all male authors who were advised not to flaunt their gender if they wanted to write from female perspectives.

The name that sits in your byline is important. Many writers, whatever gender, have used pseudonyms for various reasons: to fight societal norms, to make money, to gain a larger readership or simply because writing under another name makes them feel like a different person. Not to mention, writing under a different name ensures privacy—something that depending on what genre and politics you’re working with, could be necessary. Whatever the reason, let’s not forget the context.

Banner image: Adam, Flickr

Front page image: Kevin Dooley, Flickr

Ideas

Ideas