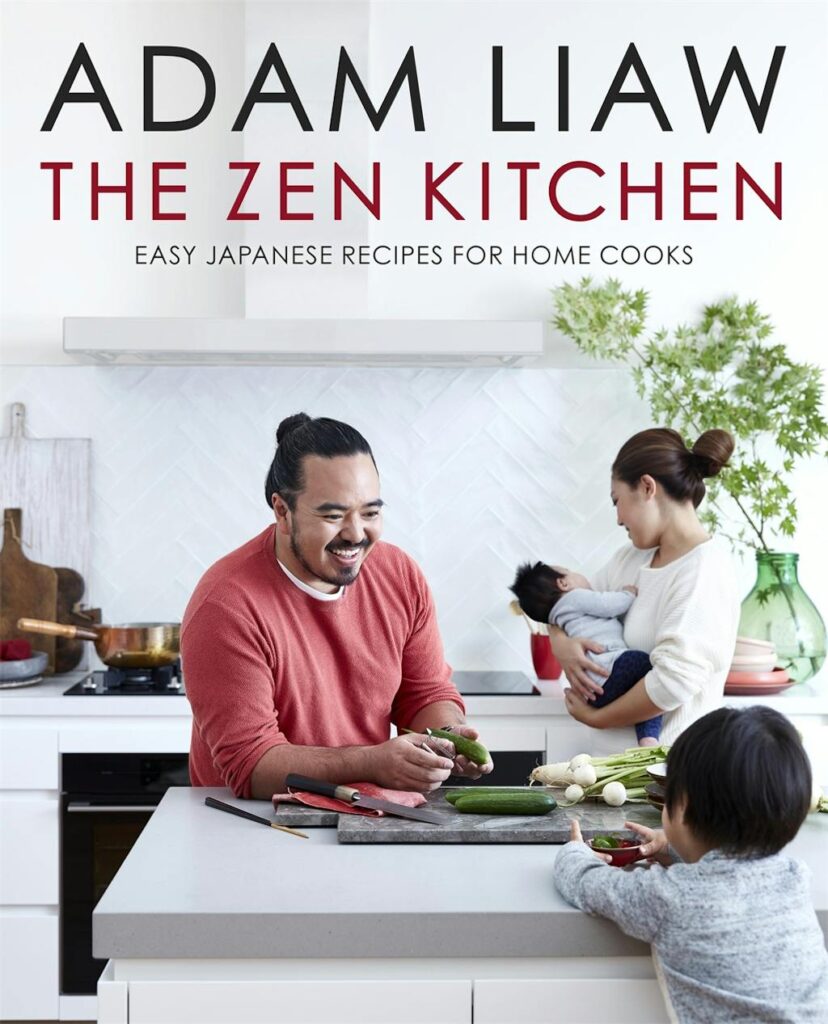

The Zen Kitchen

This is a review of Adam Liaw’s The Zen Kitchen: Easy Japanese Recipes for Home Cooks.

Too often cookbooks are treated as instruction manuals – a list of DIY projects that focus heavily on method rather than motivation. While of course this is a vital element of the cookbook’s purpose, it misses an opportunity to construct a narrative.

In Adam Liaw’s latest cookbook, The Zen Kitchen: Easy Japanese Recipes for Home Cooks, he gives the reader an understanding not just of traditional Japanese recipes, but of a whole philosophy of both cooking and living.

In his introduction Liaw, appointed a Goodwill Ambassador for Japanese Cuisine by the Japanese government in 2016, explains his mission to put Japanese food ‘in context of the culture it’s entwined with so completely’:

‘When you cook the dishes from this book, try to look beyond just the recipe, as each one is a part of a bigger cultural picture. A piece of grilled fish can be just a quick dinner, but it can also be an act of kindness, a philosophy of health, a lesson in patience, a chance to share a story, and a window into another way of thinking.’

While The Zen Kitchen is structured using the traditional divisions of a cookbook including breakfasts, seafood, meat, vegetables, Liaw’s recipes are given context as to how they fit within both the meal as a whole and across the entire day. For example, ichijyuu sansai (the combination of ‘a soup and three dishes plus a bowl of rice and a plate of pickles’) is described as a way of eating, rather than a separation of main meal and sides, and can be eaten as breakfast, lunch or dinner. The eater should take bites from across the plate, rather than focussing on one component at a time, but the cook also has the freedom to prepare components to their own taste, the structure providing a guideline rather than a set menu.

Woven throughout The Zen Kitchen are Japanese proverbs that help us to understand how tradition and philosophy inform the Japanese diet. Harahachibu ni issha irazu, an ode to avoiding excess, comes just before a series of recipes focused on cooking whole fish in different methods. The conscious pagination here is a stark contrast to Western-style meals which often view eating whole animals or large cuts of meat as an indulgent feast, rather than an act of restraint.

Restraint is a common theme in Liaw’s recipes, seen across both portion size as well as the use of seasoning ingredients and sugar. Taking time to let a sauce reduce to intensify existing flavour, rather than adding more salt, is one example of a cooking approach that shows care and dedication, rather than the Western approach which Liaw comments has become overly scientific: ‘The Japanese diet doesn’t rely on restrictive exclusions to communicate a message of good health. Good health is inherent to the cuisine.’

Balancing this restraint is a focus on community. From sharing food across the table in recipes such as nabemono, a pot of flavoured broth used to cook raw meat and vegetables at the table, to eating locally-sourced vegetables as a way of connecting with and supporting your neighbours. Tai mo hitter ha umakarazu – eaten alone, even sea bream loses its flavour.

There is also a strong sense of place throughout Liaw’s recipes, showing a connection to both seasonal cooking as well as to local ingredients. Throughout the book Liaw makes mention of how recipes are varied across the regions of Japan, such as the Sukiyaki of Beef and Asian Greens, where Liaw recreates the Kansai style from Osaka where beef is quickly fried to impart a stronger caramelised flavour before having seasoning added, whereas in Tokyo’s Kanto region the seasoning is added to the meat first before being simmered for a more delicate flavour.

Amidst all the purity and restraint of the recipes in The Zen Kitchen Liaw balances this with his recipe notes which show his passion for particular meals such as Mille Cake or the comforting winter stew made from Kingfish and Daikon. But what really sets the tone for these recipes among the broader narrative are Liaw’s anecdotes from the family table. What he loves to cook for the family. What his kid loves to eat. What he cooks for a weekend breakfast compared to a quick meal after work.

By sharing himself as well as his thorough research and appreciation for Japanese culture, Adam Liaw has created a cookbook that feels personal and relatable, but which carries a narrative in a way that sets it apart.

[ad_2]