Noëlle Janaczewska on finding inspiration in the archives and how to research your next project.

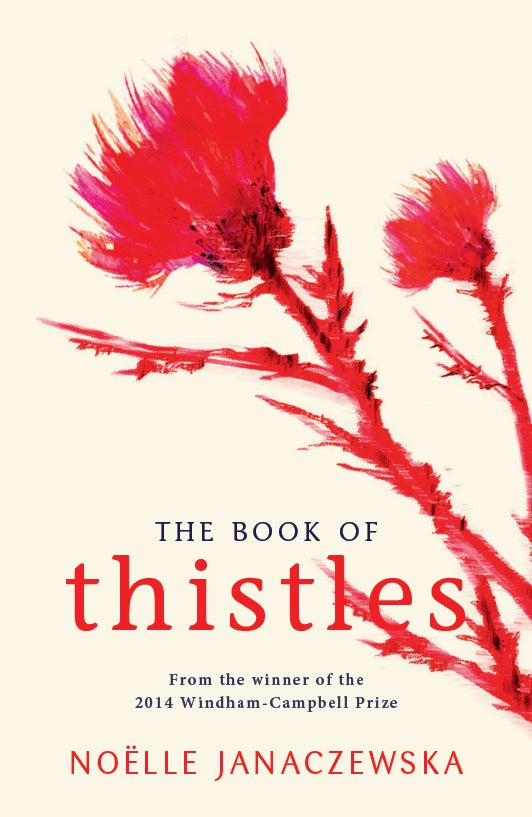

Noëlle Janaczewska knows how to research. A Sydney-based playwright, poet and essayist, her book The Book of Thistles (UWA Publishing, 2017) delves deep into the archives to tell a story like no other. At Writers Bloc, we know that whether historical fiction, memoir or journalism, a budding writer is bound to rub up against research sooner rather than later. So we sat down with Janaczewska so she could show us the way into (and out of) the archives.

Could you tell us a little about your book, The Book of Thistles?

The Book of Thistles is—yes, about thistles, but it’s about a lot more. It’s about distance and belonging, about migration, about theatre. It’s about missing voices and gaps in our story-scapes. It’s about recipes that begin: take twelve bottoms and boil your artichokes tender (artichokes are members of the thistle family).

Part accidental memoir, part environmental history and part exploration of the performative voice on the page, The Book of Thistles book fuses essay, monologue, poetry, digressions and archival collage.

What first attracted you to the subject matter?

The Book of Thistles was a long time growing. Its seeds—I’ll stick with the botanical analogy for the moment—came from several sources, but most importantly from a radio commission, a nonfiction cum personal essay script called Weeds Etc for ABC Radio National—back when ABC Radio National still had space for such work. By the time Weeds Etc went to air the thistles had taken over. Hard to resist a plant called ‘yellow melancholy’. Hard to resist the desire to discover more about nineteenth century Australia’s proliferating Thistle Acts. Because if the Dutch had tulip mania in the seventeenth century, Australia had thistle panic in the nineteenth.

Thistles have defied containment. Defied the law. Defied farmers and gardeners and municipal authorities. Defied humankind’s attempts to eradicate them. I find this defiance tremendously attractive. In a world where so many once human tasks are being delegated to other entities, where writers are increasingly viewed as ‘brands’ or ‘content providers’, I like to think that the crafting of phrases, the arranging of words on pages both paper and electronic, has become in itself an act of defiance.

Could you talk us through your research process?

I don’t have a set method. Almost everything I write—plays, radio scripts, essays, poetry—involves research, and that research process is different each time. I’m particularly interested in speculative histories and in what’s missing from official records or overlooked in mainstream narratives, so I find myself drawn to incidentals, to footnotes, asides, throw-away comments, contradictions and absences. These offer an imaginative space, a space for suggestion rather than argument, a space for fiction to meet fact.

What were some of the greatest challenges you encountered when conducting your research?

I love researching, so my biggest challenge was knowing when to stop, knowing when enough was (more than) enough. I over-researched, succumbed to a kind of ‘research fever’. In part because I’m curious and I like finding out things, which is OK, but the danger was that it let me feel that I was progressing the work, without actually composing drafts.

I’m not a botanist. My interest is in environmental history and in the social and cultural life of thistles. But I had to understand enough biology to make sense of what I was reading. Plus a thistle isn’t a single species. The word itself covers a large group of plants (over 350 species) and is also the vernacular name given to a number of lookalike plants which aren’t, botanically speaking, thistles, but look the part. Australia has a handful of native thistles, but you probably wouldn’t recognise them as such because they’re spineless. And the plant we call Afghan thistle, a WA native, isn’t a thistle at all, but more closely related to the potato.

For a writer embarking on a research-heavy project - whether it’s nonfiction or historical fiction or something else entirely - where would you recommend starting? And what resources might they find valuable?

Find a place to start—something that sparks your interest—pull a few threads and see where they take you. Then go beyond Google and into less charted territory ...

This is how American historian Robert Darnton puts it:

‘I have pursued what seemed to be the richest run of documents, following leads wherever they went and quickening my pace as soon as I stumbled on a surprise. Straying from the beaten path may not be much of a methodology, but it creates the possibility of enjoying some unusual views, and they can be the most revealing.’

Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre: And Other Episodes in French Cultural History, (New York: Basic Books, 1984)

Archives, libraries, databases, interviews, field trips are obvious places to start. But other less traditional ways of researching are also worth exploring. For one play I wrote I made a series of twenty-two A4 collages, using mostly found images (advertising leaflets, circulars, free magazines, waste paper, etc.) as a way to clarify a structure, identify voices/characters, and kick-start the writing process.

Katerina Bryant

Katerina Bryant is a writer based in Adelaide and Writers Bloc's Writing Development Manager. Her work has appeared in the Griffith Review, Kill Your Darlings and The Lifted Brow, amongst others. She tweets at @katerina_bry.