In this ideas piece, Cameron Colwell looks at how longform fiction expands the scope for more nuanced exploration of important topics.

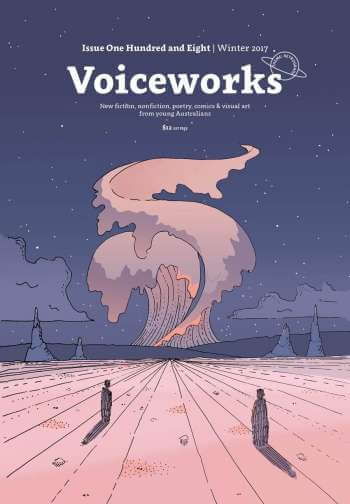

In its latest issue, #108, youth literary magazine Voiceworks published its first longform piece of short fiction. Earlier in the year, in addition to its usual callout for stories ringing in at 3,000 words or less, the magazine opened up the field to longer work, asking for pieces between 7,000 and 10,000 words.

The first story published as part of this initiative is Paul Dalla Rosa’s ‘Day Spa.’ It’s a complex, well-composed story of the kind that Voiceworks has come to excel in: Of-the-moment, harsh, and filled with moments of clear insight into the mind of its protagonist, Charlotte. Charlotte works with Eric, her colleague at a clinic for those with chronic pain and related issues, at a high school-based institute that is now in danger of being shut down due to lack of funding. We learn about her history with her condition, and are toured through her everyday life: The ebbs and flows of her closest relationship (which is with Eric), dinners with her sister (who thinks she is indulgent and exaggerating her condition), and her classes with the children who visit the institute: “Their conditions were vague and undefined but disabling all the same. They were weird, had frequent mood swings, and were allowed to stay home without doctor’s certificates.”

'Day Spa' is one of my favourite kinds of short story, which is the kind that makes me lose my breath because I resonate with it, hard. I have dyspraxia, a fairly obscure condition, which like chronic pain is invisible and poorly understood by professionals. I’ve also been involved with the education sector and witnessed what the continually draining funding pool does to people. 'Day Spa' deals with chronic pain, funding cuts and the seemingly ever-diminishing facilities of the public school system. These are issues not often deemed worthy of being explored in art, considering that their rather long-term, largely unseen impacts are perhaps difficult to dramatise. That said, to thrust them into the mental landscapes of readers who otherwise might not think on these topics is an admirable task that the story takes on brilliantly. The longform format allows this impressively wide range of issues to be delved into, in a non-superficial way, rather than only touched upon lightly.

The general tone of Charlotte’s story is reminiscent of someone resignedly telling you their problems because they need to, not because they want to, and while too tired to look for pity: “Eric had a stroke at sixteen and spent the next twenty years painfully reawakening the right side of his body. I was different. I woke up in my early twenties with a headache that never went away.”

The story being told in the voice of someone who has experience with disability is likely the reason this work avoids most of the clichés that tend to crop up in stories focused on this area. There’s no inspirational ending, and Charlotte is not the poster person for anything: Beyond the nebulous definition of ‘chronic pain’ Dalla Rosa talks about in the interview published in the same issue of Voiceworks, 'Day Spa' is vague about specific conditions.

Probably the thing that sticks in my mind most strongly about the story is its dead-on portrayal of abled people who just do not get disability that looks disparate from how they’ve seen it portrayed 90% of the time in modern media. The title itself refers to a line of dialogue from the school treasurer who makes the decision against funding the institute: “Frankly, it seems like a day spa kind of deal,” she says, evoking the way that disability accommodations such as subtitles or modified keyboards for those whose hands don’t work are often seen—that is to say, as unnecessary luxuries that are a privilege, rather than a right. There’s also the all-too-familiar mentions of how people function in “the real world” from Charlotte’s sister.

The invisibility of Charlotte’s disability coupled with the fact she is a woman also impact on the way she is treated. Even the agents of the medical institution are incredulous, as detailed by their response towards her: “I told him I’d seen neurologists who’d told me they do not work at the centre for imaginary diseases, and myofascial pain specialists who told me, in off-the-record whispers, that I probably just needed to get laid. I told him I’d spoken about legal action and how every single time they had called my bluff.” Snippets like these make material and solid the disabling features of society that most people don’t think about. The falseness of the sense of omniscience people often place in the medical sector is laid bare—“He asked if I wanted to help explain the science behind chronic pain to teenagers and late adolescents. I said I didn’t know the science and he said no-one really did.”

Without gushing about how much I love Voiceworks, which, like, I could do for days on end, I’ll just quickly add that I’m so grateful they saw the opportunity to publish this kind of work and took it.

I doubt the nuance that 'Day Spa' draws its strength from would’ve come through if it had been a story under 3,000 words. There’s not enough space for this kind of story to be told often in Australia: Dalla Rosa mentions in the interview that “Australia has an obsession with three-thousand-word short stories and I don’t really know where it comes from.” My guess, both from the perspective of a writer and an editor—I’m Creatives Editor for Grapeshot, my university magazine—is the practicalities of publication. Still, it’s weird that this specific limit is the one that’s been generally agreed upon, especially for publications open to youth like Voiceworks. The volume of submissions coming in seem infinite, nobody in publishing is paid enough (or at all), mostly everybody in the lit mag game is overworked. Asking people who read dozens upon dozens of 3,000 word short stories to read more seems like a bit much. It’s hard to figure out whether low word limits in submissions is just something I’m imagining, or a vague suspicion I hold that’s fairly common in everyone I decide to bring it up with. Tilting at Windmills: The Literary Australian Magazine 1968-2012, Phillip Edmonds’ survey of literary magazines across that time period, unfortunately does not among its many notable attributes record any rises or falls in word count submissions in the history of Australian literary magazines. The shift to digital publication of many magazines that feature short stories with often nebulous word count limits also makes it difficult to work out the size of this particular quirk in our literary culture.

I sort of have to wonder, though, as someone with multiple stakes in the game, if it’s too much of a stretch to say that being at all aware of Australia’s literary ecology means being in a constant state of longing for all the stories that aren’t told? It’s not just longing, though: I’m grumpy about all the subtlety that gets lose in the edits that happen to ensure that a story is short enough. I’m frustrated that, for a fact, that not enough is being done by our whole culture to support our marginalised artists. I’m agonising about the apathy from both politicians and the general public towards the arts while at the same time I understand there are So Many Other Things To Worry About—and I’m sad about the solace that is so seldom afforded to writers dealing with day jobs and partners and domestic labor etcetera.

Modern life is brutal. I can’t solve that, and I could never expect my fellow editors to pick up even more weight by making stories like 'Day Spa' the norm rather than the exception, though. Still, I think it’s worth reflecting on what kind of stories we could see from our young artists if we had more room to work with.

You can buy Voiceworks #108, Retrograde here.

Cameron Colwell

Cameron Colwell is a writer, critic, and poet from Sydney, Australia. He has appeared on a panel at National Young Writers Festival, has had work published in The Writer's Quarterly, Heaps Gay, and The Star Observer, and was the 2013 winner of the Mavis Thorpe Clark award for a collection of short stories. His Twitter is @cameron___c and his work can be found at www.neonslicked.wordpress.com